First things first, before we dive into the history of the macaron let’s get the most important thing out of the way – how to pronounce macaron vs. macaroon. Although both are equally delicious, the way it is said could mean the difference between happiness and (possibly) disappointment.

If you are looking for a small round cake with a meringue-like consistency, made with egg whites, sugar, and powdered almonds and consisting of two halves sandwiching a creamy filling – then you want a macaron.

Pronounced – (/ˌmækəˈrɒn/ MAK-ə-RON,[French: [makaʁɔ̃] – where “-ron” is pronounced like “gone”. However, if you want a cookie that’s typically made of shredded coconut stirred into whipped egg whites and sugar – an iteration of meringue that’s not as light as a macaron – then you want a macaroon – where “-roon” is pronounced like “moon.”

As with many foods, there seems to be confusion as to when the macaron first appeared.

Origins and Early History

The first possible sighting of a macaron is believed to be in 827. According to Dan Jurafsky’s article Macaron, Macaroons, Macaroni – The Curious History in Slate magazine, Arab troops from Ifriqiya, which is modern-day Tunisia, landed in Sicily and set up a Muslim emirate. This period saw the introduction of numerous technologies including the introduction of new foods, such as lemons, rice, and pistachios, into Europe. Among the cultural treasures they brought were an array of nut-based sweets from the medieval Muslim world. These included fālūdhaj and lausinaj—almond-paste candies wrapped in dough. These treats were adapted from sweets enjoyed by the Sassanid Shahs of Persia hundreds of years earlier to celebrate the Zoroastrian New Year.

According to a Swiss digital archive dedicated to the history of baking, almond biscuits made their journey from al-Andalus (modern-day Spain) to Marrakesh (modern-day Morocco) during the early 11th century. This migration was credited to Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the sultan and inaugural monarch of the Almoravid dynasty. These biscuits gained popularity as a staple treat served during Ramadan festivities.

Other says that the journey of the macaron begins in Italy, with roots dating back to medieval times. The term “macaron” derives from the Italian word “maccarone” or “maccherone,” which refers to a paste or dough made from ground almonds – similar to “macaroni.” These early versions were simple almond cookies, very similar to today’s amaretti.

In the 16th century, the macaron crossed borders and arrived in France, brought by the pastry chefs of Catherine de’ Medici when she married King Henry II in 1533. These early French macarons were quite different from the modern version; they were single-layered almond meringue cookies, crunchy on the outside and soft inside, without any filling.

However, one problem with this story after a meticulous examination of historical records by some historians documenting the personnel employed by Catherine from her arrival in France until her passing showed no mention of any Italian chefs in her service. So … there’s that.

Evolution in France

However, the culinary encyclopedia Larousse Gastronomique (1988) states that macarons originated in a French monastery in Cormery during the 8th century, around the year 791. Legend has it that these pastries were designed to resemble the navels of monks.

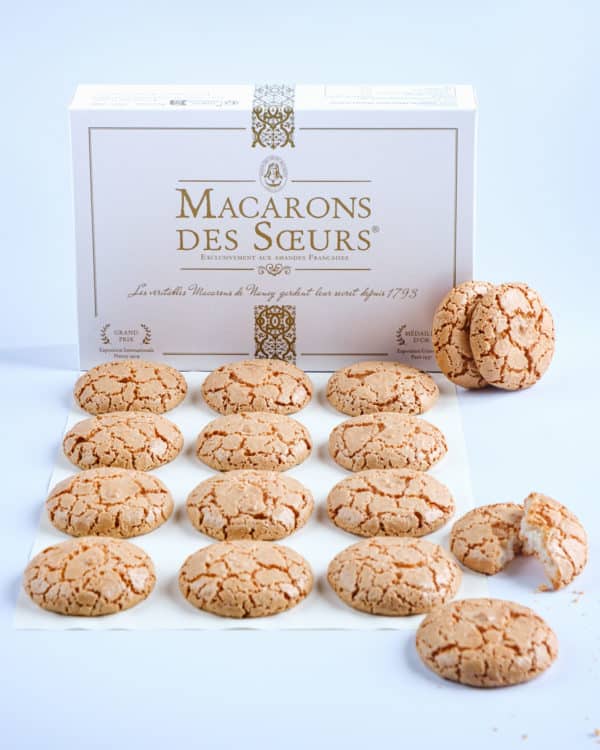

A pivotal moment in the history of the macaron occurred during the French Revolution in 1789. According to legend, two Carmelite nuns, Sister Marguerite Gaillot and Sister Marie-Elisabeth Morlot, sought asylum in Nancy. To support themselves, they began baking and selling macarons. These nuns, who became known as the “Macaron Sisters,” helped popularize the macaron in the Lorraine region, where the tradition continues today. However, these are essentially the top half of their more famous counterpart.

“It’s possible one of the nuns brought some form of the recipe with them upon joining the sisterhood and then perfected it. In 1792, a decree abolishing religious congregations led to their expulsion from the abbey,” writes Hugh Tucker, BBC Features Correspondent. “The nuns fled and took refuge with a local doctor, supporting themselves by making and selling their macarons.”

Since then, these macarons have been sold in the town ever since.

“When Marguerite died, Marie passed the secret to her niece and the business remained in the family for another three generations. The business was passed to the Aptel family in 1935 and the premises moved from the site of the original pâtisserie to the location it occupies today. Jean-Marie Genot purchased the business in 1991 before passing it, and the secret of the macaron, to his son Nicolas in 2000.”

“The recipe and the secret are passed on orally, they’ve never been written down, and, in the contract with the new pâtissier, both sides swear to never teach the making to anybody else,” says Nicolas Genot, the current owner of Maison Macarons des Sœurs. “The owner of the pâtisserie is the only one who makes the macaron, alone and away from prying eyes.”

In 1952, the city of Nancy honoured them by giving their name to the Rue de la Hache, where the macaron was invented.

The Modern Macaron

It wasn’t until the 1930s that macarons evolved into the familiar sandwich cookies, featuring fillings such as jams, liqueurs, and spices. Pierre Desfontaines, the grandson of Louis-Ernest Ladurée, is credited with creating the modern macaron around 1930 at the Ladurée patisserie in Paris, although another baker, Claude Gerbet, also claims to have invented it. Regardless who took or is given credit, the innovative idea was to sandwich two almond meringue cookies together with a creamy ganache filling. It was initially known as the “Gerbet” or “Paris macaron.”

Ladurée’s macarons became a sensation due to their unique texture—a delicate, crisp shell with a moist, chewy interior—and their variety of flavors and vibrant colors. This innovation set a new standard for macarons and transformed them into the sophisticated treat we know today.

Global Popularity

In the latter half of the 20th century, the macaron’s popularity began to spread beyond France. In the 1980s and 1990s, as global travel became more accessible and culinary tourism flourished, visitors to France would often bring back boxes of macarons, helping to spread their fame internationally.

The 21st century saw an explosion in the macaron’s popularity worldwide. Social media, particularly platforms like Instagram, played a significant role in this global phenomenon. The visually appealing nature of macarons—with their rainbow of colors and elegant packaging—made them perfect for sharing online, further fueling their international demand.

Renowned pastry chefs such as Pierre Hermé elevated the macaron to new heights. Often called the “Picasso of Pastry,” Hermé pushed the boundaries of macaron flavors and fillings. His innovative combinations, such as rose and lychee, olive oil and vanilla, and even foie gras, challenged traditional notions and attracted a global following.

Chef Pierre Hermé is also the President of the Coupe du Monde de la Pâtisserie.

Cultural Impact

Today, the macaron is more than just a dessert; it is a cultural symbol of elegance and the artistry of French patisserie. Macarons are often associated with luxury and are a popular choice for special occasions, high-end events, and as gifts. They are prominently featured in films, fashion shows, and are a staple in upscale patisseries around the world.

Despite their international popularity, the craft of making macarons remains a delicate art. Authentic macarons require precision and skill, with many patisseries holding their recipes and techniques as closely guarded secrets. The process involves creating the perfect meringue, achieving the right consistency for the batter (known as macaronage), and mastering the baking process to avoid common pitfalls such as cracked shells or hollow interiors.

In Portugal, Spain, Australia, France, Belgium, Switzerland, New Zealand and the Netherlands, McDonald’s sells macarons in their McCafés (sometimes using advertising that likens the shape of a macaron to that of a hamburger). McCafé macarons are produced by Château Blanc, which, like Ladurée, is a subsidiary of Groupe Holder, though they do not use the same macaron recipe.

Outside of Europe, the French-style macaron can be found in other countries including Canada and the United States.

Variations of Macarons Around the World

France

Several French cities and regions claim long histories and variations, notably Lorraine (Nancy and Boulay), Basque Country (Saint-Jean-de-Luz), Saint-Émilion, Amiens, Montmorillon, Le Dorat, Sault, Chartres, Cormery, Joyeuse, and Sainte-Croix in Burgundy.

Macarons d’Amiens, made in Amiens, are small, round-shaped biscuit-type macarons made from almond paste, fruit and honey, which were first recorded in 1855.

The city of Montmorillon is well known for its macarons and has a museum dedicated to them. The Maison Rannou-Métivier is the oldest macaron bakery in Montmorillon, dating back to 1920. The traditional recipe for Montmorillon macarons has remained unchanged for over 150 years.

The town of Nancy in the Lorraine region has a storied history with the macaron. It is said that the abbess of Remiremont founded an order of nuns called the “Dames du Saint-Sacrement” with strict dietary rules prohibiting the consumption of meat. Two nuns, Sisters Marguerite, and Marie-Elisabeth are credited with creating the Nancy macaron to fit their dietary requirements. They became known as the ‘Macaron Sisters’ (Les Soeurs Macarons).

India

Thoothukudi in Tamil Nadu has its own variety of macaroon made with cashews instead of almonds, adapted from macarons introduced in colonial times.

Japan

Macarons in Japan are a popular confection known as マカロン (makaron). There is also another widely available version of makaron which substitutes peanut flour for almond and a wagashi-style flavouring. The makaron is featured in Japanese fashion through cell phone accessories, stickers, and cosmetics aimed towards women.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, Luxemburgerli (also Luxembourger) are a brand name of macaron made by Confiserie Sprüngli in Zürich. A Luxemburgerli comprises two disks of almond meringue[with a buttercream filling in of many available flavors. Luxemburgerli are smaller and lighter than macarons from many other vendors.

United States

Pastry chefs in the US have expanded the classic cookie to include such varied flavours as mint chocolate chip, peanut butter and jelly, Snickers, peach champagne, pistachio, strawberry cheesecake, candy corn, salted pretzel, chocolate peanut butter, oatmeal raisin, candy cane, cinnamon, maple bacon, pumpkin, and salted caramel popcorn.

South Korea

In addition to macarons, fat-carons (뚱까롱, thick macarons), also called ttungcarons, were invented and became popular in South Korea. The bakers intentionally overfill the macaron filings and later decorate them as well. The appearance can resemble more to that of a small ice cream sandwich.

Conclusion

The history of the French macaron is a fascinating journey of culinary evolution and cultural adaptation. From its simple origins in Italy to its sophisticated reinvention in France, and finally to its status as a global delicacy, the macaron has continually evolved while maintaining its essence. It stands as a testament to the creativity and craftsmanship of pastry chefs throughout history, and continues to captivate dessert lovers around the world with its unique blend of flavors, textures, and visual appeal.

Refernces:

Wikipedia