Butter, a kitchen staple for centuries, is integral to the world of baking and pastries. Its unique composition and characteristics significantly influence the texture, flavor, and overall quality of baked goods. Understanding the science behind butter can help bakers harness its full potential to create mouthwatering treats.

Before delving into the science of butter and its significance to bakers, pastry chefs, and culinary professionals, let’s first explore the rich history of this essential ingredient.

The History of Butter

Butter, a beloved staple in kitchens around the world, has a rich and storied history that dates back thousands of years. Its journey from ancient times to modern-day kitchens is a fascinating tale of culinary evolution, cultural significance, and technological advancements.

Ancient Beginnings

The history of butter begins with the domestication of livestock, particularly cattle, sheep, and goats. Some evidence suggests that people were making butter as early as 8000 BCE, shortly after the domestication of these animals in the Fertile Crescent region. The earliest methods of butter production were likely discovered accidentally, perhaps when milk was stored in animal skins and naturally churned during transport. This accidental discovery led to the development of intentional butter-making techniques.

While the other evidence of butter-making dates back to around 6,500 BCE, based on milk fat residues found on pottery in Northwest Turkey. It’s believed that ancient people consumed butter, cheese, and yogurt rather than raw milk due to widespread lactose intolerance.

According to ButterJournal.com, butter was a food for celebration in the Bible, first mentioned when Abraham and Sarah offered three visiting angels a feast that included meat, milk, and the creamy yellow spread.

Early Cultures and Butter

Mesopotamia and Egypt: In ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, butter was not as prevalent as other dairy products like cheese and yogurt due to the hot climate, which made butter spoil quickly. However, these cultures did use clarified butter (similar to ghee), which has a longer shelf life.

Ancient India: In India, butter, particularly ghee, has been a staple for thousands of years. Ghee is clarified butter that has had the milk solids removed, making it more stable and suitable for cooking in the hot climate. It holds significant religious and cultural importance, used in cooking, rituals, and traditional medicine. Hindus have been offering ghee to Lord Krishna for at least 3,000 years.

Ancient Rome and Greece: The Greeks and Romans were aware of butter, but it was not a central part of their diet. They considered it a food of the northern “barbarian” tribes, preferring olive oil instead. The Greeks used butter medicinally and cosmetically. In ancient Rome, it was used medicinally for coughs and joint pain.

By the Middle Ages, butter had become popular across northern Europe especially in the colder northern regions where it could be stored more easily. . It was favored by peasants as an affordable source of nourishment and by nobility for its rich flavor. By the 10th century, butter was a common food in Scandinavian and Germanic cultures and became a crucial part of their economy. In Ireland, butter was so important that merchants opened a Butter Exchange in Cork to regulate trade.

Monasteries played a crucial role in the production and spread of butter. Monks perfected the art of butter making, and it became a valuable trade commodity. By the Renaissance, butter was well-established in European cuisine. It became particularly popular in France and England, where it was used in cooking, baking, and as a spread.

“In France, butter was in such high demand by the 19th century that Emperor Napoleon III offered a large prize for anyone who could manufacture a substitute,” states ButterJournal.com. “In 1869, a French chemist won the award for a new spread made of rendered beef fat and flavored with milk. He called it ‘oleomargarine,’ later shortened to just margarine.”

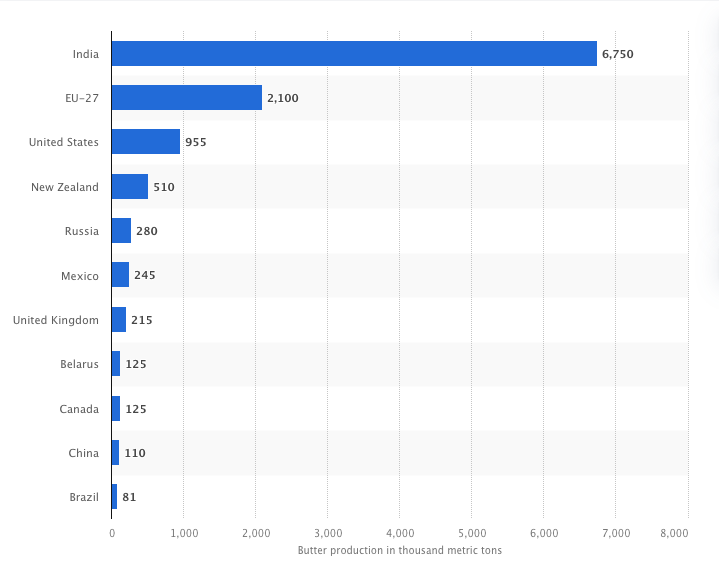

Butter production remained largely a manual process until the 19th century when industrialization began. The United States pioneered butter factories in the 1860s, leading to large-scale production. As of 2023, India was the top butter producing country, producing over 6.7 million metric tons (Statista.com) The European Union came second, with approximately 2.1 million metric tons of butter being produced.

The first butter factories appeared in the United States in the early 1860s, after the successful introduction of cheese factories a decade earlier.

The invention of the mechanical cream separator in the late 19th century allowed for more efficient separation of cream from milk, leading to increased butter production.

In the late 1870s, the centrifugal cream separator was introduced, marketed most successfully by Swedish engineer Carl Gustaf Patrik de Laval

- Pasteurization: The introduction of pasteurization helped improve the safety and quality of butter by eliminating harmful bacteria.

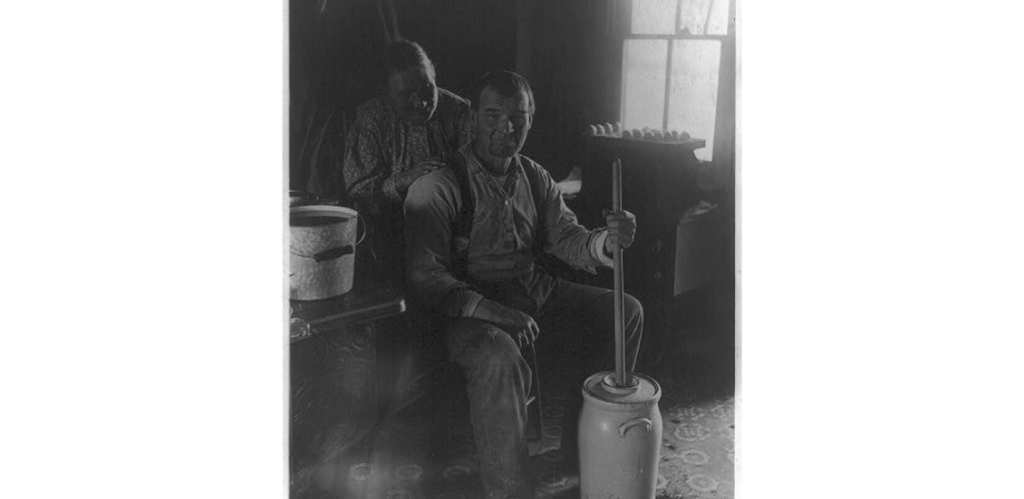

- Churning Machines: Mechanical churns replaced traditional hand-churning methods, making butter production faster and less labor-intensive.

- Mass Production: The development of refrigeration and better transportation methods enabled the mass production and distribution of butter, making it more accessible to a broader population.

In recent history, butter faced challenges during the Great Depression and World War II due to shortages and rationing. The rise of margarine and low-fat diets in the late 20th century also impacted butter consumption. In the 1980s, dieticians and the USDA began promoting a low-fat diet, leading to butter falling out of favor. By 1997, consumption had dropped to 4.1 pounds per capita per year. However, butter has since made a comeback as research has shown it to be less harmful than previously believed.

Today, butter is a ubiquitous ingredient in kitchens worldwide, cherished for its rich flavor and versatility. Its production has become a highly refined process, with a focus on quality and consistency. Butter is available in various forms, including salted, unsalted, cultured, and clarified, catering to different culinary needs and preferences.

Butter Making

At its core, butter-making relies on the principle of phase inversion. In cream, tiny fat globules are surrounded by membranes of phospholipids and proteins, which keep them dispersed in the water-based liquid. The key to transforming this emulsion into butter is agitation, typically through churning or shaking. When cream is vigorously shaken or churned, several important changes occur:

- Fat globule collision: The fat globules in the cream are forced to collide with each other repeatedly.

- Membrane disruption: These collisions cause the protective membranes around the fat globules to break down.

- Fat aggregation: As the membranes rupture, the exposed fat molecules begin to stick together, forming larger clumps.

- Phase separation: Eventually, enough fat globules combine to form a solid mass (butter), separating from the liquid (buttermilk).

The science of butter-making also involves temperature control. Cream at room temperature (around 20°C or 68°F) is ideal for butter-making, as the fat is partially crystallized, which aids in the formation of a stable butter structure.

Composition of Butter

The composition of butter reflects its origins and production process. Typically, butter contains:

- 80-82% fat

- 16-17.5% water

- 1.5% salt (in salted varieties)

- 1% milk solids (vitamins, minerals, and lactose)

Interestingly, the fat in milk is about 70% saturated and 30% unsaturated. This composition contributes to butter’s semi-solid consistency at room temperature and its melting behavior.

This specific ratio of fat to water and milk solids is what gives butter its unique properties and makes it so valuable in baking.

Role of Butter in Baking

1. Texture and Structure

Butter’s fat content plays a crucial role in determining the texture of baked goods. Here’s how:

- Tenderness: Fat coats the flour particles, inhibiting gluten formation. This results in a tender crumb, which is especially desirable in cakes, cookies, and pastries.

- Flakiness: In laminated doughs like croissants and puff pastry, cold butter is layered between sheets of dough. During baking, the water in the butter evaporates, creating steam that causes the dough to puff up and form flaky layers.

- Moisture: Butter’s water content provides necessary moisture to doughs and batters, ensuring a tender and moist final product.

2. Flavor and Aroma

Butter contributes a rich, creamy flavor that is difficult to replicate with other fats. During baking, the Maillard reaction and caramelization occur, both of which enhance the flavor and produce a desirable golden-brown color:

- Maillard Reaction: This chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars occurs at higher temperatures, resulting in the complex flavors and brown coloration of baked goods.

- Caramelization: The sugars in butter caramelize during baking, adding sweetness and depth to the flavor profile.

3. Leavening and Volume

In certain recipes, butter contributes to the leavening process:

- Creaming Method: When butter is creamed with sugar, air is incorporated into the mixture. These air pockets expand during baking, resulting in a light and airy texture, as seen in cakes and cookies.

- Steam Leavening: In laminated doughs, the water in butter turns to steam during baking, helping to create volume and lift in the pastry layers.

Types of Butter and Their Uses

Most butter in the United States is made from pasteurized cream, which means the cream has been heated to kill bacteria. The label “sweet cream butter” indicates that the butter was made with pasteurized cream. However, raw (unpasteurized) butter can still be legally produced and sold in certain states under specific regulations.

1. Unsalted Butter

Unsalted butter is the preferred choice for baking because it allows bakers to control the amount of salt in their recipes. It has a pure, sweet cream flavor that enhances baked goods without altering their taste.

2. Salted Butter

Salted butter contains added salt, which can act as a preservative and flavor enhancer. It is not commonly used in baking because the added salt can interfere with the precise measurements required for successful recipes.

3. Cultured Butter

Cultured butter is made from fermented cream, which gives it a tangy flavor and higher butterfat content. This type of butter can add a unique depth of flavor to pastries and is often favored by artisan bakers.

People have been told that the higher the butterfat the better the butter and that you should “use the highest quality butter with the most butterfat” for baking. While this is true in some cases it isn’t true all the time.

In the United States, butter sold in supermarkets typically contains 80% butterfat. European and European-style butters usually have up to 83% butterfat. Butter from small, local dairy farms often has even higher butterfat content, sometimes between 85% and 86%.

However, that doesn’t mean you should be using 85% or 86% butterfat for everything. If you’re looking for a delicious butter to spread on toast, go for the highest percentage you can find. But for baking it’s perfectly acceptable to use an 80% butterfat butter and even better if it’s just a bit higher – around 82%-83% butterfat.

Chef Jenny McCoy from the Institute of Culinary Education writes, “Butter with a very high butterfat percentage tends to cause cakes and bread to rise less and pastries to be less light and flaky.”

Handling and Techniques

1. Temperature Matters

The temperature of butter is critical in baking:

- Cold Butter: Used in pie crusts, puff pastry, and biscuits, cold butter helps create flaky layers. It should be kept as cold as possible to ensure that it doesn’t melt into the dough before baking.

- Room Temperature Butter: Ideal for the creaming method, where butter is mixed with sugar to incorporate air. The ideal temperature is generally between 65° and 67°F (18° and 19°C), which is cooler than the typical room temperature of 72°F. You can use a thermometer to check the temperature in the center of the butter block, or you can press your finger into it to see if it holds an indent. When pressed, it should be soft but not so soft that it becomes greasy. Room temperature butter should be cool to the touch, but still flexible enough to whip.

- Melted Butter: Used in recipes like brownies and some cakes and cookies, melted butter provides moisture and density without incorporating air. Lending a richer, deeper, nuttier flavor, brown butter also works well in some baked goods.

2. Cutting In Butter

For pastries and pie crusts, butter is often cut into the flour until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs. This technique ensures that the butter is evenly distributed, creating a tender and flaky texture.

3. Creaming Butter and Sugar

The creaming method involves beating butter and sugar together until light and fluffy. This process incorporates air, which helps leaven baked goods and creates a light, tender crumb.

If your recipe called for creaming butter and sugar together there is a right way and a wrong way to do it. And there is even a science to it. If you have ever wondered why your baked goods didn’t come out as they should have, one of the reasons could have been in the creaming stage.

When creaming butter and sugar, there are several common pitfalls that can affect the outcome of your baked goods:

- Using butter that’s too cold or too warm: The butter should be at room temperature, soft enough to leave an indentation when pressed but not melted. If it’s too cold, it won’t incorporate air properly, and if it’s too warm, it won’t hold the air bubbles.

- Not creaming for long enough: Many bakers underestimate the time needed for proper creaming. It typically takes 5-7 minutes of beating to achieve the right consistency. Insufficient creaming can result in a dense final product.

- Creaming at the wrong speed: Using too low a speed won’t incorporate enough air, while too high a speed can cause the mixture to heat up and lose structure. A medium to medium-high speed is usually ideal.

- Using the wrong sugar: Granulated sugar that’s too coarse can result in a grainy texture. Using superfine or caster sugar can help achieve a smoother consistency.

- Incorrect proportions: Using too much sugar in relation to the butter can result in a mixture that doesn’t cream properly.

- Not scraping the bowl: Failing to scrape down the sides of the bowl during creaming can lead to uneven incorporation of ingredients.

- Overbeating: While it’s important to cream thoroughly, overbeating can cause the mixture to become too warm and lose its structure.

- Adding eggs too quickly: If eggs are added too fast after creaming, it can cause the mixture to curdle or separate.

- Opening the oven too early: While not directly related to creaming, opening the oven before the cake is set can cause it to collapse, resulting in a dense texture.

- Using low-quality butter: Butter with a high water content or added ingredients other than cream can affect the creaming process and final texture.

Conclusion

Butter is a fundamental ingredient in baking, cherished for its ability to enhance texture, flavor, and structure. Its unique composition and properties make it indispensable in the creation of a wide range of baked goods, from flaky pastries to tender cakes. Understanding the science behind butter allows bakers to use it more effectively, achieving delicious and consistent results every time.

Sources:

ButterJournal.com

MilkyDay.com

Science Buddies, (2013, June 20). “Scrumptious Science: Shaking Up Butter.” https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bring-science-home-shaking-butter/

Center for Dairy Research. “Butter Science 101: Basic Lipid Chemistry and Butter Structure.” https://www.cdr.wisc.edu/butter-science-101

Massachusetts Farm to School. “How to Make Butter (and the Science Behind How It’s Made).”

https://www.massfarmtoschool.org/guide/how-to-make-butter/